A Classic Film’s Timeless Reminder: Policing Must Get Back to the Basics

How a 1950 crime thriller highlights the enduring truth that technology should enhance—not replace—the core principles of effective law enforcement.

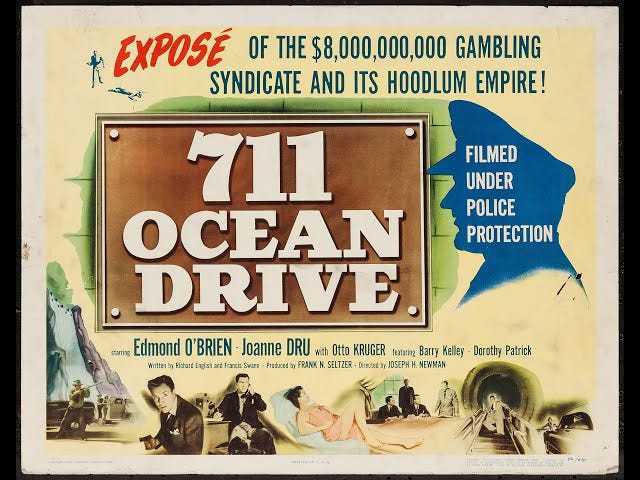

The cinema provided a reminder of how policing needs to get back to the basics. Nothing drew me to the title or the description, so it was sheer luck that I found this hidden treasure from 1950: 711 Ocean Drive on Prime Video.

If you watch it this weekend, you will thank me for it. Despite adult themes, overall it is very family friendly. I was immediately struck by how the unmarked sedan went screaming out of the precinct building to get the gangster squad detective to the airport to fly to Las Vegas with a warrant to catch the criminal. Hopefully today, there is policy in your organization preventing running code in city traffic to catch a plane - but that’s missing the point.

The plot in a nutshell is the talented Mal Granger (played by actor Edmond O’Brien) is persuaded to leave his technology job at the phone company to work for a syndicate of bookies who employ him to enhance their own wire system. The climax of the film takes place at Boulder Dam (today’s Hoover Dam) with exceptional cinematography. At that time, the dam - completed two years ahead of schedule in 1936 - just 14 years prior to the film’s release - represented a collection of firsts and human achievement milestones. The dam itself was a technological breakthrough and became the heartbeat of Las Vegas as we have come to know it today.

Solutions offered through technology

We plainly see new technology being introduced to law enforcement, whether it is gait recognition or A.I. using surveillance feeds to create focus on abandoned suspicious packages. The New York (City) Police Department coined the phrase ‘real time crime center’ in July 2005. The department had a received a philanthropic grant of $10M to get it off the ground. At that time, mobile high-speed data remained on the distant horizon. Reading the articles at the time, I was fully jazzed with the idea. My belief then was as soon as we can scale this appropriately and speed up the mobile data flow, I believed that we could reduce crime by half and incarcerate many of the people who were predisposed to commit more than a single murder.

“My beliefs may have been modified over the last 20 plus years, yet I still continue to believe that is the only key to crime reduction is the removal of prolific criminals from communities.”

Technology has fundamentally changed how we can see, hear, and respond. Real-time crime centers (RTCCs), license plate readers (LPRs), predictive analytics, and even artificial intelligence analyzing patterns have added a layer of speed and focus that was simply unattainable two decades ago.

“It is unbelievable that we are catching people who we wouldn’t have caught before, yet crime is still rising.”

This should be the priority of all law enforcement executives but instead, flying in the face of reason, they will present that all violent crime is down and possibly concede that some category of property crime has inched up. Dr. Travis Yates has it right and makes a stellar point:

“When was the last time you heard of a police chief getting fired because of an increase in crime?”

Tech in the daily life of a cop

Today we push information directly to the screen of the cop nearest to the crime in progress. But all that capability still hinges on someone who has received substantial training showing up, knowing the community context, asking the right questions, and writing a clean, factual report. The instruments are impressive, but they’re only as effective as the humans wielding them.

Despite these advances, we must resist the temptation to believe technology is a substitute for presence, instinct, or experience. A camera can’t sense the tension in a room or the subtle shift in someone’s story. An algorithm might flag an area for increased patrol, but it’s the officer walking or cycling that beat—knowing which door to knock on or which kid just needs a little guidance— is the who makes the real difference.

The foundation of policing still rests on communication, decision-making, discretion, and competent authority. Technology must be an amplifier, not a replacement, for the fundamentals that define effective law enforcement. Artificial Intelligence should be viewed as a stepstool rather than a ladder, something that expands your reach but doesn’t do the job for you.

AI is good at math, but police officers are good at people and get increasingly better with more earned wisdom and experience.

Regardless of era or technological advancement, there is no substitute for the core values of integrity, courage, and resourcefulness. Cinematic images from 75 years ago underscore an essential truth: policing thrives when officers embody personal responsibility, keen observation, and direct engagement with their communities. The strength of policing lies in officers who, beyond reliance on technology instinctively assess and swiftly respond to dynamic situations on the street. There’s no substitute for that.

Best practices and traditions

In preserving the best traditions, agencies must ensure that officers remain skilled communicators, critical thinkers, and ethical decision-makers, astute in bridging the gap between digital insights and real-world solutions. The lasting value of old films lies not only in nostalgia but in their vivid reminders of enduring principles that modern policing must never abandon. It is great to look back at five digit calling codes (example: Kenmore 9392, Fort Wayne, IN) to operators to connect your call.

It is also worthy of note that people were pulled over by a simple red 75-watt red spotlight, and knew they were being pulled over day or night, without two or three million lumens of blue, red, or white intense LEDs.

In my youth, I traveled many miles through California during the time CHiPs was at its height of popularity. I noted that none of the California Highway Patrol cars that I saw on patrol or at weigh stations (or when we were pulled over) had roof mounted light bars like the show. CHP cars were absent of radar at the time and would pace speeders, even from auxiliary service roads with frequently calibrated speedometers. They did much more than the characters in the show with far less resources. In the trucking community nationwide, while not well liked, the CHP had forged a reputation of efficiency in enforcement.

Early in my career, I developed friendships with troopers of the Florida Highway Patrol. One of my friends was a female trooper assigned a 5.0 Mustang with a five-speed manual. I asked her if she called for assistance for prisoner transport and she said most of the time she would just buckle them in the front passenger seat and take them to the booking office. Her colleagues with Crown Vics were issued cars without prisoner partitions, but they were permitted to purchase and install them out of pocket. Any current law enforcement executive with any fiscal responsibility background can compare merely the costs of body camera programs, vehicle upfitting including cameras and locating systems, and real time crime intelligence centers to the beginning of their careers and see how costs of getting an officer on the road have changed in the past few decades.

Technology enhances law enforcement capabilities, amplifying efficiency and precision, but it must always complement—not overshadow—the timeless, human-driven practices that form the backbone of effective policing. We say that technology can identify patterns, highlight suspects and speed investigations, yet every time I have had an analyst who can nail down a predictive pattern, it comes from a top-notch analyst who could have and would have figured that out a simpler way.

Technology can never replace the trust earned through face-to-face interactions, the empathy communicated during victim interviews, or the wisdom gained from experienced mentorship within the department. In preserving the best traditions, agencies must ensure that officers remain skilled communicators, critical thinkers, and ethical decision-makers, capable of bridging the gap between digital insights and real-world solutions. Let’s ensure that every intern, cadet, explorer, and potential recruit understands what policing is truly about—before they ever pin on a badge.

Please keep all our law enforcement officers in your prayers.

Roland Clee served a major Florida police department as a Community Service Officer for more than 26 years. His career included uniformed patrol, training, media relations, intelligence, criminal investigations, and chief’s staff. He writes the American Peace Officer newsletter, speaks at public safety, recruiting and leadership conferences and helps local governments and public safety agencies through his business, CommandStaffConsulting.com. His work is frequently featured on LawOfficer.com, the only law enforcement owned major media presence in the public safety realm.

References:

https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/navigating-future-ai-chatgpt/

I gotta watch this one. So many people misunderstand things like forensic evidence, for example. Most cases are solved by old fashioned police work. The more advanced stuff takes time and really serves to confirm the old fashioned method’s work. In cold cases, the new technology solves stuff we couldn’t solve before, but most fresh cases still rely on the basics.

I'm intrigued, and will be looking for this film.

You make important points, namely that technology can never replace what the men and women of law enforcement bring to the table, or replicate their innate desire to protect and serve.